Jun 19, 2009

Imagine the Freedom

And who hasn’t, at some point in their lives, when looking up at the stars with an empty beer bottle at his side, or huddling at the bus stop with sleet hitting her in the face, imagined the freedom? The romantic allure of the lottery is undeniable — so many of life’s problems can be solved with money, and winning the lottery is the easiest way to get lots of cash, fast.

For some people, simply eliminating one’s most odious debts would be enough to fuel their fantasies, but for most of us the dream of winning the lottery means winning big — tens of millions, or, as a friend of mine once put it, “enough that I don’t have to budget.” Vast sums of money mean freedom from obligations, for one, and freedom to live as one pleases, for another, and perhaps most titillatingly of all, the freedom to indulge one’s every ridiculous whim. There’s a lot of cultural baggage packed into those three desires, and while it would be easy to attribute our fascination with the lottery to moneylust alone, there’s more than just a fascination with or envy of the lifestyles of the wealthy at work here. It’s the faint whiff of attainability attached to a huge lottery score that keeps us coming back for more. No matter how many of life’s doors are closed to us, the possibility of winning the lottery, however slim, always remains — if you have two bucks and can get to the store … but it’s up to you to pick the right numbers.

There’s an even deeper resonance to the massive lottery win. The idea is woven into the fabric of our culture, taking on an archetypal, even mythical weight. Like the bolt of lightning from the heavens (to which it is so often compared, at least in terms of probability) the life-altering lottery win ties us in a metaphysical way to ideas of class, chance, and fate.

![]()

There’s a catch ….

The lottery is nothing if not democratic: it offers each ticket an equal chance of winning. But you can’t win if you don’t play, and does everyone stand an equal chance of playing? There’s the old maxim that lottery tickets are a tax on people who failed highschool math. But before examining the demographics of just who is buying lottery tickets, let’s take a look at the math in question (if you find mathematical pedantry hebetude-inducing, by all means skip to the next section).

There are a couple of instructive formulæ for calculating the overall prudence of playing the lottery. The first is a simple calculation of the expected returns — although it’s only “simple” if you make certain conditions and assumptions. Expected returns are essentially the total potential gains multiplied by the odds of winning — for example, if I told you that for a dollar I’d let you flip a coin, and if it came up heads I’d give you $3.00, the expected returns are $1.50, which is the total possible gain ($3.00) multiplied by the odds of winning (½). Since the buy-in is $1.00, this looks like a good bet; given enough rounds at these odds, you should, according to the statistics, make about 50% profit on your total investment.

There are a couple of instructive formulæ for calculating the overall prudence of playing the lottery. The first is a simple calculation of the expected returns — although it’s only “simple” if you make certain conditions and assumptions. Expected returns are essentially the total potential gains multiplied by the odds of winning — for example, if I told you that for a dollar I’d let you flip a coin, and if it came up heads I’d give you $3.00, the expected returns are $1.50, which is the total possible gain ($3.00) multiplied by the odds of winning (½). Since the buy-in is $1.00, this looks like a good bet; given enough rounds at these odds, you should, according to the statistics, make about 50% profit on your total investment.

With the lottery, it’s obviously much more complex; first you have the problem of secondary prizes and free tickets, not to mention Encore. Then there’s the issue of what happens when someone else shares your numbers and the jackpot is split. For the purposes of the rest of the investigation, we’ll set that aside — so just imagine that each lottery ticket buys you a chance at winning the jackpot alone and there’s zero chance of splitting the winnings. Assuming you’re trying to match 6 of 6 numbers out of a pool of 49, your odds of holding a winning ticket are 1 in 13,983,816. [1]

In Canada, Lotto 6/49 tickets cost $2.00 per board. With our simplified math, you can see that for the expected returns to be a positive number, the jackpot should be at least $27,967,632.00 before potential gains multiplied by the odds of winning are larger than the cost of playing. In other words, if the jackpot is over $28 million, they’re going to be paying out more than $2.00 for each possible combination of 6 digits.

That should make it easy to weigh the costs against the risks: if the jackpot is above $28 million, you statistically stand to gain more than you stand to lose. But what these simplified calculations of expected returns don’t factor in is the fact that the expected returns are not global; because they are consolidated into a single jackpot, they are in fact binary, all or nothing. And since the odds of winning are so vanishingly small, you would, in reality, expect to win nothing.

But perhaps the lure of the big, big payout makes the tiny risk of losing $2.00 seem worth it. Sure, you’ll probably lose, but you can’t lose more than $2.00, and you stand to gain millions. While that might seem to rationalise a ticket purchase, consider also the relative value of the $2.00 cost of entry, given the minute odds of winning — not relative the jackpot, but relative the money at your disposal. Given those unfavourable odds, if you had, say, $4.00 left on this earth, wouldn’t blowing half your wad be inadvisable? Wouldn’t you be better off saving it for a hot meal? Sure, on paper the expected returns may be $2.05, but in reality you’re far more likely to end up with $0.00.

Fortunately, there is a way to calculate the relative merits of a risky investment against the relative risks of losing your investment. Called the Kelly criterion, after inventor J. L. Kelly Jr., this formula weighs the potential damage against the potential gains while also considering the cost of entry as a fraction of one’s total bankroll to arrive at the best possible wager, mathematically speaking. Specifically, it’s

![]()

where f is the appropriate fraction of one’s bankroll to wager in order to maximise one’s earnings, b represents the odds returned on the wager (usually in terms of b:1 — in the case of a lottery jackpot this would represent the amount of the jackpot divided by the price of the ticket), p is the probability of winning (in this case 1 in 13,983,816), and q is the probability of losing (or 1 – p).

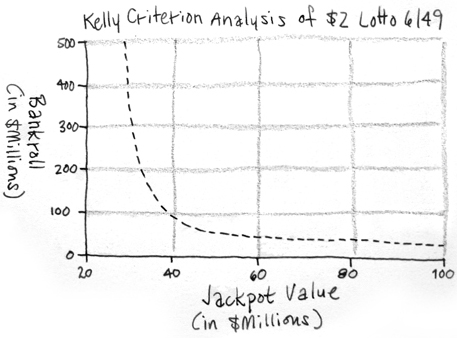

While the odds of winning (and losing) remain constant with a lottery draw, we do have two variables here — one for the size of the jackpot, and one for the size of the bankroll (in other words, the amount of money one has to devote to buying lottery tickets); with two variables one can graph f in terms of the relation between the size of our bankroll and the potential gains (f in this case is $2.00 as a fraction of one’s total bankroll, the y axis):

Anything to the right of the dotted line is a good investment; anything to the left puts undue strain on your bankroll given the risks involved. As you can see, a jackpot of about $27 million is asymptotic; no matter how high you extend the graph, the line will never reach the $27 million mark, because as already stated, below that figure expected returns will always be less than the buy-in. [2]

But what’s more striking is that the graph shows exponential decay, with diminishing losses somewhere around the $40 million jackpot mark — but only for people with $100 million to spend. In fact, if you have less than a million, the jackpot would have to be several hundred million dollars before parting with even $2.00 of your own money could be called a smart risk. Even with this foggy math, which assumes the impossibility of sharing a jackpot, a lottery ticket purchase is statistically inadvisable for all but the insanely wealthy.

![]()

Who’s playing the lottery?

Knowing that it’s a bad investment from a statistical point of view raises the question of who decides the play, and why. As for the “who” half of the question, there are two camps into which the statistics fall. Depending on whom you ask, they may say that no single group is particularly drawn to the lottery. According to the OLGC’s own website, all demographics, based on age, education, ethnicity or income, play at roughly the same rate: almost two thirds have played before and plan to play again, and more than one in five play weekly. In the US, the figures are similar, where the average American spends roughly $200.00 on the lottery each year, with lotto players skewing slightly to the wealthier and more educated end of the spectrum. But while these studies show lotto players are more likely to be employed and have a slightly higher income — a trend across several studies — the trend is not a pronounced one. [3]

Other studies, while not directly contradicting those numbers, have indicated that people from lower income brackets play more frequently, suggesting that the conditions of poverty lead one to put more stock in the lottery. One study, conducted at a Greyhound bus station, found that a group of subjects made to feel poor were more likely to buy tickets than a control group. A second study tried reminding people that while inequalities persist in jobs and education, everyone has an equal chance of winning the lottery; those people went on to buy tickets at three times the pace of a control group. [4] Indeed, lottery ticket sales go up during times of economic hardship, and areas within a county or state with higher than average rates of poverty see higher than average lottery ticket sales as well. [5]

Reconciling those two families of studies seems to suggest that lottery playing is the domain of people who can most easily afford it — the more disposable income you have, the more you spend on the lottery. For people on very tight budgets, lottery tickets might literally take away from food and shelter. But for anyone with a certain amount of discretionary income, the question of whether to play the lottery may be secondarily influenced by the intensity of one’s perceived poverty — whether that is feeling less affluent than one’s visible peers, or struggling with new financial problems, or even just feeling that winning the lottery represents the fastest way to reach one’s goals. It may go without saying, but one thing all lottery players have in common is a belief that their lives would be improved by large sums of money; it follows that the more room for improvement, the more likely one is to act on that belief to the extent that one’s budget allows.

Ultimately, there is a random sampling of lotto players about which we can gather a fair amount of information: lotto winners. Because we can see that the people who win the lottery represent a cross-section of the population at large (both lottery players and non-players), we can deduce that everyone playing represents a cross-section of the population as well. There’s a lot of material out there implying that lottery players are predominantly unintelligent or poor; if that were the case, lottery winners would also be predominantly unintelligent or poor. In North America, lottery winners are required to reveal their names and locations, and quick glance at the bios of lottery winners shows that, if anything, they are more likely to be employed (or retired!) and well-off if not quite affluent. [6][7] At the very least we should discard the negative stereotypes we may hold about lottery players.

![]()

Cognitive Leaps

We can say with a fair degree of confidence that lottery players, in terms of background and intelligence, are average. We have shown, mathematically, that buying a lottery ticket is irrational, at least from a gaming perspective. It follows that average people make glaring ratiocinative errors. But there are some cognitive effects that can mislead anyone, no matter how intelligent, into irrational behaviour. [8]

- Operant Conditioning with Variable Reinforcement

Conditioning is not a difficult concept to grasp: reward and punishment. Behaviours that are rewarded we repeat, and ones that are punished, we tend not to. Psychologists have known for years that to maximise the effects of conditioning, the reward schedule must be varied (the same does not necessarily hold true for punishment). That is, if you are rewarded every third time you perform an action, the effect of the reward to motivate you will deteriorate over time. Vary that — giving reward after 3 times, then 5, then 2, and so on — and the motivation is intensified. The lottery does give positive reinforcement, in small payouts like free tickets or $10.00 winnings, and these payouts are random. Not knowing if the very next play could be a reward keeps people coming back.

- The Availability Heuristic

Very few people get murdered by burglars in their homes — but the few who do are reported on the news, so it seems like it happens more frequently than it does. As a result, we’re probably more afraid of being murdered in our homes than we need to be. We tend to think that just because we hear about something often, it happens often; we assume that notoriety is the same as prevalence.

The same effect is at work with lottery winners. We hear about them all the time, and this accrual of anecdotes leads us to believe that this is an everyday occurrence. While it does happen regularly, what is not factored into our assumptions is the size of the population these news articles draw from. Even though they pick a winner every few days, on a winners-per-million basis, it’s still exceedingly rare.

- The Gambler’s Fallacy

Part intuition and part superstition, the gambler’s fallacy is the belief in “streaks,” runs of luck, or being “overdue” for a win. A string of losses just makes a win that much more likely, according to this belief. The problem with this belief is not hard to spot; if lottery wins are like coin tosses, where the results can be predicted statistically, then yes, it is possible to be overdue for a win — but only after playing the lottery 13,983,816 times. At twice a week, that would take about 134,460 years. Then you’ll be overdue for a win — statistically speaking.

- Selective Memory

Remember all those times the subway pulled out of the station just as you were running up to it? Of course you do. Remember all those times you waited around until the subway arrived, and then you got on? Probably not. As a result, you probably feel, like most people, that the train is always pulling away just as you arrive — even though you know, rationally, that you stand an equal chance of arriving at every stage of the train’s progress. But when the train pulls away on you, you get pissed off, and start forming opinions about the behaviour of subway trains that subsequent examples will confirm, even if they’re comparatively rare.

The point being: we tend to remember things that stand out, and that confirm what we already hold to be true. When you are already susceptible to the availability heuristic, thinking that winning the lottery is more common than it actually is, you may start collecting memories of all the stories you’ve heard of people who have won. Nobody remembers stories about all the people who didn’t win.

These cognitive gaps certainly allow people to put more faith in playing the lottery than they otherwise might, evaluating their chances more rationally. The desire to win goes without saying: as a culture and as individuals, we value money. This desire for money, coupled with these cognitive leaps, means we often end up believing what we want to believe. But why do we want to believe this in the first place? Is there a greater mystique to winning the lottery that transcends simply collecting wealth?

![]()

For proof of the resonance of huge lottery wins in our culture, we don’t have to look any further than our myths, or urban legends. The major ones fall into a handful of categories. There’s one notable aberration: the diner waitress who received millions for a tip left in the form of a lottery ticket (a true story, incidentally). [9] The rest are uniformly bleak: the man hit by a truck and killed just hours after winning the lottery, [10][11] the guy who showed his winning ticket to his friends at a bar and lost it before it could be redeemed, [12] the woman whose jealous husband killed her to inherit her fortune, [13] and the man who missed playing his numbers one time, and after his numbers inevitably came up, was driven by despair to commit suicide. [14]

The spectre of Fate hangs over all these stories. There is a lesson or lessons to be taken away from each of them. The unspoken message is that these people simply weren’t meant to win; Fate had it in for them from the beginning. Not only are these people no better off than they were before, they’re left far worse off — desolate at the loss of what might have been, or worse still, dead.

The spectre of Fate hangs over all these stories. There is a lesson or lessons to be taken away from each of them. The unspoken message is that these people simply weren’t meant to win; Fate had it in for them from the beginning. Not only are these people no better off than they were before, they’re left far worse off — desolate at the loss of what might have been, or worse still, dead.

Closely tied to our urban legends of lottery winners and near-winners is the platitude about the people who do win, and live to spend their money: they inevitably end up miserable and / or broke. Either they spend their money in a matter of weeks and end up broke or in jail, [15] or live to sit on their money at the expense of their ties to everyone around them. [16] We are led to believe that winners have to distance themselves from the universally jealous family and friends who come clawing after their money, and are forced to shut themselves off from the world and the people they knew. Let’s not forget the scrutiny of the ravenous media, and the anxiety that comes both with monumental life changes and the responsibility of looking after a fortune of that size. It will, simply put, ruin your life. [17] There is even, perhaps unremarkably, a book on the subject. [18] Then there are the studies — mostly rumoured, seldom published — which purport to show that not only are lottery winners not happier than the average person, they’re actually less happy. [19]

This may be just a matter of sour grapes — we console ourselves and each other, reassuring ourselves that we are better off not having won anyway, repeating exactly what we want to believe. Or it may be the echo of that old warning, “Be careful what you wish for.” There is a moralising tone to these parables: greed is bad. It is natural to desire wealth, and natural impulses are to be fought. The “Be happy with what you have” tenor to all these threads reveals a disturbing counterpoint, a message not about what you have, but what you will never have.

![]()

The dream of the easy lottery win is, after all, just a distillation of another even more pervasive dream: the American dream. I use the term loosely; the axiom that hard work and enterprise can pay off for anyone is more defining of capitalism itself than of American culture. The American dream is ultimately about class mobility — in the past, our futures were predetermined from birth, but today, through the liberalising influence of social mechanisms like anti-nepotism laws and affirmative action, and the entrepreneurial opportunities capitalism gives us, our futures are the product of our hard work, determination, and ambition.

While I believe that is largely true, there is a certain amount of class rigidity in North America that remains obfuscated by a cultural investment in the belief that we live in a total meritocracy. We believe — because it is preferable to believe — that our success or failure in life is the result of our choices alone; it is uncomfortable to think that people who skip from one class to the next are the rare exception rather than the rule, and that for the great majority of us, we are born into the caste we will work in our entire lives.

Part of this obfuscation is due to the fact that the lower- and middle-classes define themselves strictly in terms of affluency (I use these terms of class with the consciousness of the circular logic inherent in their subjective self-application). That is, we see class as an issue of how much wealth we have, and to a lesser extent what privileges that wealth brings us, and this supports the idea that our social strata are not static or delineated. Social classes defined in terms of wealth are necessarily continuous and therefore somewhat arbitrary.

Another way of defining class is in relation to labour — specifically, is an individual required to sell his labour for a wage? The range of people who are required to sell their labour spans a huge swath of income levels, from itinerant field workers living as wage slaves to brain surgeons and CEOs earning millions of dollars a year. Viewed in this way, the labouring class becomes much more difficult to escape; even small business owners who own the means of providing their own income are essentially bound to their work, forced to operate the business to make a living. They work for themselves, but they still work. This is distinct from the capitalist who provides the investment for production or commerce, assumes the risk on behalf of his or her workers, pays workers’ wages and collects the profit (if there is any) from the products of that labour.

There are arguably more transparent examples of class or caste systems both today and in antiquity; when class is defined socially rather than financially, the rigidity or statis of social classes is more generally acknowledged, if not perhaps embraced. In the traditional class system of England, for example, aristocracy is not a factor of money (although they usually do have money, and titles may be sold by aristocracy fallen on hard times); one would not expect that simply having lots of money would put one in the same social class as titled, club-membership-holding families whose history in the aristocracy stretches back centuries. There is a distinction between old money and new — the focus, again, is on money — but the real difference is in family history, the provenance of the money, one’s upbringing and resultant inclusion in or exclusion from social groups (note the clannishness of boarding schools and universities that persists into adulthood).

Capitalism requires the workers’ investment in the belief that they will be judged solely on their merits as a worker, that success is the product of effort and not a birthright, and that wealth is the only metric by which one’s success can or should be measured. While capitalism remains arguably the most meritocratic and therefore the most acceptable form of labour system to the liberal-minded, it does rely on a certain amount of carrot-dangling. The carrots of social advancement may be a form of misdirection if the advancement is in affluence but never in one’s position in the labour market.

![]()

There is a certain point in one’s early adult life when one realises that one was not born into privilege, that one has no birthright, that one’s only means of support is the sale of one’s labour, and that one is never going to be the next Paris Hilton or Warren Buffett. At that point, one may be forced to confront the possibility that class mobility, while it exists on paper, may turn out to be inaccessible. If that is the case, it places strain on the conception of our society as a meritocracy. [20]

If labour and merit alone are not enough to ensure that classes are fluid and mobility is open to everyone, the lottery stands as the ultimate loophole. Accessible to everyone, totally democratic, and able to instantly lift people to high degrees of wealth — and therefore social status — the lottery fulfills the promises that capitalism makes to its workers but is unable to keep, even with the liberalising mechanisms we have worked so hard to put into place.

The lottery is the stuff of fantasies about individual freedom — it’s right there in the jingle — but implicit in the question of freedom is the concern of freedom from what? The lottery not only props up the ideology of a system founded on class mobility by proposing that wealth is, in fact, potentially available to anyone — it’s also the direct result of a system that is founded on the lack of freedom that actually defines everyone in the labouring classes.

Our culture, presented to us while we are children as a perfect meritocracy where literally anyone can grow up to be President or Prime Minister, makes us a promise. Reward and punishment are used throughout our education and upbringing to mould us into workers who believe that we can get ahead through our labours. The promise is implicit, invisible even, a hegemonic haze so ubiquitous we’re seldom even aware that this promise exists; we take it for granted that we will be hired based on our merits as applicants, we will be rewarded financially based on our merits as workers, and our contribution to society will be recognised not only monetarily but in our social status and ultimately the class status we obtain. For better or for worse, the labour market can’t exist without this promise, but it’s a promise it can’t really keep — at least not for everyone. But as long as the lottery runs, we will always be able to look to people who have chosen the right numbers and hope that we can someday join the wealthy. If there is a lottery, one need never admit that this could be as good as it gets.![]()

![]()

FOOTNOTES

[1]

http://www.joe-ks.com/archives_jan2004/Lotto_Odds.htm

A calculation of the odds of winning the Lotto 6/49.

[2]

http://r6.ca/blog/20090522T015739Z.html

An explanation of the statistics of expected returns, and of the Kelly criterion. This site is also the source for my recreation of the graph showing the statistical curve of profitability in playing the lottery.

http://www.quantwolf.com/doc/powerball/powerball.html

Some background on the Kelly criterion.

[3]

http://www.olg.ca/assets/documents/media/lottery_player_statistics_fact_sheet.pdf

Statistical information on who makes up the body of lottery players.

[4]

http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/08207/899406-298.stm

A report on a study indicating that poverty (or the sensation of poverty) makes on more likely to play the lottery.

[5]

http://www.johnlocke.org/press_releases/display_story.html?id=253

A report on a study that indicated areas with high poverty have higher levels of lotto ticket sales.

[6]

http://lotterywinnerbios.blogspot.com/

A blog that aggregates news stories and profiles of lottery winners from around the world.

While you might feel that these people are not particularly well off, I would have to disagree with you. I would identify many if not most of the people profiled at the above link as working-class; if they appear lower-class, that is probably indicative of how far the working class has fallen relative the upper-middle-class over the past few decades.

For more on that subject, I encourage you to visit here (or look up anything written by a Marxist in the last 40 years):

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/27295405/

[7]

http://palmdesert.ucr.edu/conferences/economica2007/winters-gdi.pdf

A thorough study of lottery purchasing habits in Texas, including profiles of different types of lottery players.

[8]

http://faculty.clintoncc.suny.edu/faculty/June.Foley/lottery.htm

Cognitive obstacles preventing lottery players from rationally assessing the prudence of playing.

[9]

http://www.snopes.com/luck/lottery.asp

An analysis of the urban “legend” about the waitress who received a multi-million dollar tip from a lottery-winning patron.

[10]

http://www.snopes.com/luck/dead.asp

An analysis of the urban legend about a man killed hours after winning a sizable sum in the lottery.

[11]

http://www.snopes.com/luck/megabucks.asp

An analysis of the urban legend about a man killed hours after winning an obscene sum in the Powerball lottery.

[12]

http://www.snopes.com/luck/pocketed.asp

An analysis of the urban legend about a man who lost his winning lottery ticket before having an opportunity to redeem it.

[13]

http://www.nationalpost.com/news/story.html?id=314008

A newspaper article about a man accused of murdering wife to inherit her lottery winnings.

[14]

http://www.snopes.com/luck/lottosuicide.asp

An analysis of the urban legend about a man who commited suicide after failing to playing the time his numbers finally came up.

[15]

http://www.fool.com/personal-finance/retirement/2005/02/04/rats-i-won-the-lottery.aspx

An online journal article attempting to argue that people who win the lottery frequently end up broke or in jail.

This is but one example; there are far too many to even mention in this space. But to provide an example of the ubiquity of this type of conception of lottery winners, the current first return on the Google search “lottery winners” is “8 lottery winners who lost their millions” on msn.com.

[16]

http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/s_146760.html

An online journal article attempting to argue that winning the lottery ruins your life, particularly your relationships with others.

[17]

http://www.lotterypost.com/news/165079

An online journal’s profile of a reclusive multi-million pound winner, who declared “Winning the lottery ruined my life.”

[18]

http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_ss_gw?url=search-alias%3Daps&field-keywords=the+golden+ghetto&x=0&y=0

Amazon.com profile of The Golden Ghetto — a book on the subject of people who face challenges after obtaining large amounts of money in a short period, including those whose lives are deleteriously affected by lottery wins.

On the site, one review mentions that “Jessie O’Neill’s story helps give voice to hte [sic] pain and isolation that wealth can bring.”

[19]

http://moneycentral.msn.com/content/invest/forbes/P95294.asp

An online journal article presented as a statistical study showing that lottery winners are on average less happy, but which is actually an analysis of anecdotal evidence from a small number of people.

[20]

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all~content=a713845949

Not only does the lottery represent the ideal democratization of success, in that everyone has an equal chance of succeeding, but it also ties into one of materialism’s most treasured themes: individualism. There is an air of meritocracy to playing the lottery, even if it is patently superficial, simply in the fact that one has the ability to choose whatever numbers one pleases. It’s up to the player to simply be good enough or lucky enough to see what those numbers will be (or perhaps to simply want it badly enough — that seems to be the criterion cited most often by young athletes as the most crucial to their victory). If you don’t win, you have nobody to blame but yourself. If there are “metaphysical forces” at work (as the millions who bought into The Secret believe their are), it’s up to the lottery player to harness them personally.

An interesting footnote to the subject of one’s personal culpability in lottery success or failure is one’s relationship to the numbers played. Players frequently choose birthdays of loved ones, anniversaries, or other dates of importance, addresses, jersey numbers, and lucky numbers that for no rational reason the player has come to identify with on an almost spiritual level.

Seen through this lens, the act of choosing lottery numbers and consistently filling out lottery tickets can be seen as an act of self-expression (and self-expression another manifestation of freedom in our individualistic culture).

Given that our modes of consumption are among the ways we define ourselves in a materialistic culture, and especially our conspicuous consumption, the very act of spending money could be said to make us who we are. Referring back to the opening sentence: one of the joys of playing the lottery brings is the opportunity to fantasize about what it would be like to win the lottery, and more specifically, what we would do with the money if we won. I personally have had this conversation more times than I can remember and assume it’s universal among people who live in cultures with a lottery, including among those people who don’t actually play. The effect of even contemplating what one would do with a lottery win is essentially to spend the money mentally, thereby mentally defining ourselves as consumers in our idealised form. Spending money is how we exert our power in a capitalist society, so spending money in our imaginations lets us wield maximum power, and in effect lets us define ourselves and our relation to our consumer society, at least in an academic way.

So you may as well imagine the freedom; imagining it is as close as you’re likely to get.

One tangent that I was, unfortunately, unable to work into this already tangent-ridden post was a look at the history of the lottery, which dates back millennia. I was shocked to learn that not only does it go back at least as far as the Roman Empire, but they have been politically administered with the intention of raising funds for public works for just as long.

Today, in Ontario at least, lottery profits go to public works and sponsorship programs. But the idea of using a lottery to raise money for public programs probably goes back to the reign of Augustus Cæsar, who devised a lottery to pay for repairs to Rome’s infrastructure. Queen Elizabeth I approved a lottery to fund restoration of England’s harbours, and the British Museum was later founded using lottery revenue. For more tidbits, go here.

Blerg.

Double blerg.